Tannins are often used to describe a wine’s profile, but their role or what they are is usually little understood. In a sentence, tannins dry out your mouth – they are usually most noticeable after you take a sip. The bigger, bolder, and more red the wine is, the more presence they are likely to have.

In this article, we explain everything you need to know about tannins, how to appreciate them, and what they actually contribute to your wine.

What Are Tannins?

The Definition of Tannins

Tannins are chemical compounds found in plants. They are important for protecting plants from predators and may contribute to plant growth. For that reason, the level of tannins in a plant is also an important factor in deciding when to harvest. Allegedly, the word “tannin” also comes from the process of “tanning”, as tannin-rich plant extracts are traditionally used to tan leather.

How Tannins Work in Wine

When you taste a wine, tannins contribute two things: bitterness and astringency. Bitterness is a flavour, whereas astringency is more of a texture, commonly defined as how dry your mouth feels after a sip of wine. In the grand scheme of wine, tannins also contribute to ageing. As a red wine ages, tannins disappear and the bitterness softens, allowing deeper flavours to come forward.

Where Do Tannins Come From?

Tannins in Grapes

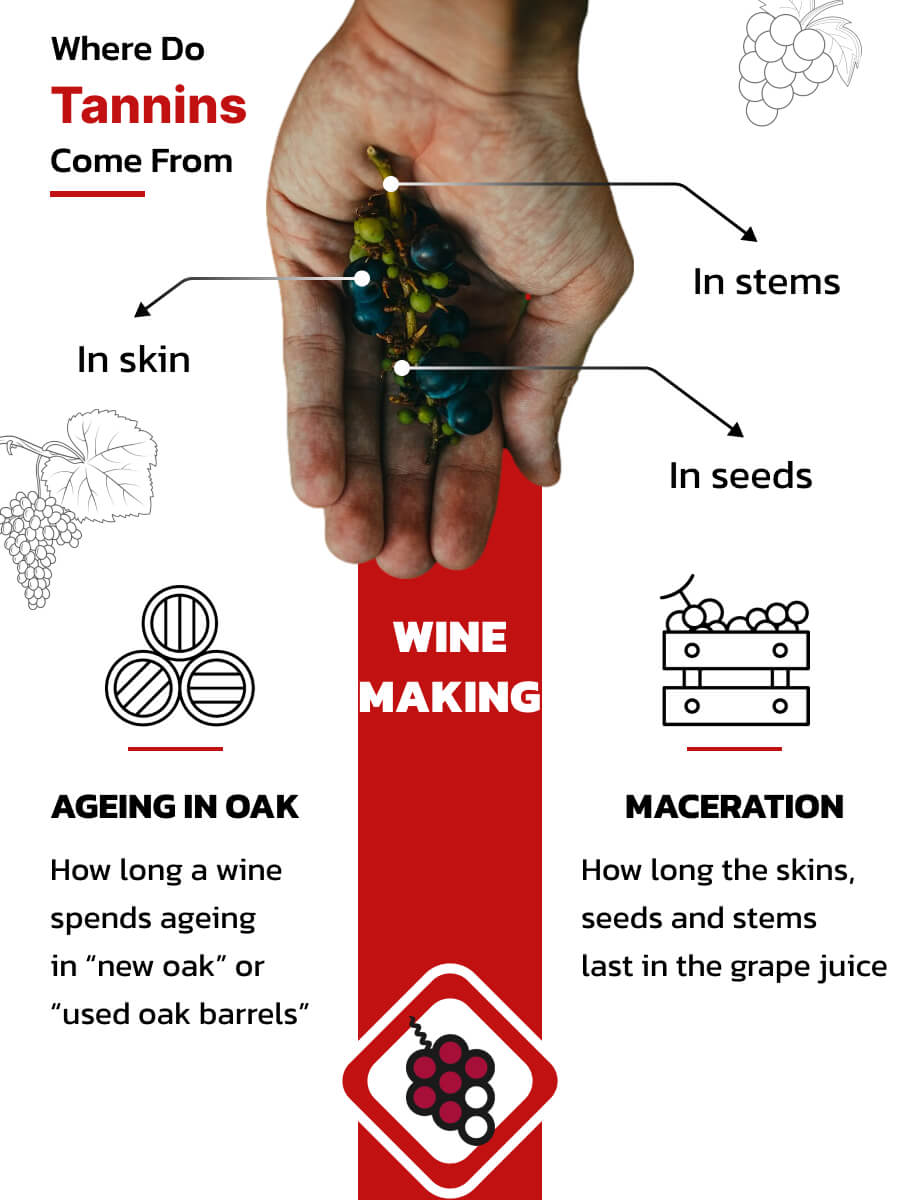

In grapes, tannins are particularly present in the skin, seeds, and stems. This is why red wines are more tannic than white wines. White grapes are rarely fermented with their skins, while red wines can be made with stems, seeds, and skins all included.

Winemaking Techniques

Throughout winemaking, tannins leach into the grape juice, adding structure and texture. Several winemaking processes influence the levels of tannins – for example, how heavily macerated the grapes are (in simple words, how much they have been “stomped”), whether the stems are left in or out during fermentation, and how long the wine spends ageing in oak barrels.

Tannins Beyond Grapes

Beyond the grapes themselves, tannins are also present in the walls of oak barrels. How long a wine spends ageing in these barrels is another important factor. Over time, oak tannins will seep into the mixture, adding a distinctive bitter, almost leather-like taste, and potentially increasing the wine’s potential for ageing in the bottle.

When we see buzzwords like “new oak” or “used oak barrels”, this also gives us hints towards what a wine’s tannic structure is like, or what the winemaker’s goal was with this particular wine. Newly constructed oak barrels contribute more tannins, with more of a raw, bitter profile, while oak barrels that have already been used for fermentation offer more subtle tannins. This is why winemakers often use a mixture of both new and old, as they seek a balanced level of tannins.

How Tannins Affect the Taste of Wine

Astringency and Bitterness

Have you ever made a cup of black tea and forgotten to take the tea bag out, or forgotten about it entirely? When you try drinking the cold cup of tea later, you find that it’s incredibly strong, and the flavour is bitter and puckers your mouth slightly (this sensation is astringency). That’s the influence of tannins, seeping out from the tea leaves over time, and it’s a good example for understanding how they work in wine.

Whether you enjoy tannins is a personal thing. Some people enjoy the mouth-puckering quality, some people don’t, and for some people, too many tannins can upset their stomach. However, they are an excellent indicator of how long a wine can be aged.

In young versions of many wines, like the famous Barolo from Northern Italy, the tannins can be too strong to be enjoyable, and they soften as the wine ages in a cellar. So, a good balanced amount of tannins (which does not necessarily mean a lot) is often seen as a marker of quality, and whether the wine is ready to be enjoyed.

Tannins and Food Pairing

There’s a reason why red wines, meat, and cheese are a match made in heaven, and it’s largely because of tannins. When we’re eating and drinking, tannins bind with and are absorbed by the protein and fat in food. This creates a symbiotic relationship – your wine becomes less astringent, allowing deeper flavours to come through, and revealing whole new aspects to the wine. On the other hand, the tannins also cleanse your palate of fats and proteins, allowing the true flavour of the meat, cheese, or whatever else you happen to be eating to shine through. Tannin-rich wines work particularly well with protein-rich and fatty foods, while low-tannin wines can be saved for lighter meals.

Types of Wine and Their Tannin Levels

Due to the thickness of their skin, their stems, or simply the environment they grew in, some grapes are naturally more tannic than others. In this section, we will explore some of the most iconic examples from each tier of tannins, and give you some buzzwords to attempt to describe what they feel like. Disclaimer: they may not make sense until you try them yourself.

High-Tannin Wines

Some of the best-known high-tannin wines include Cabernet Sauvignon, Barolo, Sangiovese, Mourvèdre, and Malbec. So why are these wines more tannic than others? Let’s take Nebbiolo (used to make Barolo and Barbaresco wines) as an example; it is widely regarded as the most tannin-rich winemaking grape in the world. Its home is Piedmont, a cool and foggy region, with relatively poor soils. These conditions lead to grapes with thick skins – and not only that, but Nebbiolo grapes are comparatively small to other winemaking grapes, so the ratio of pulp to skin is high. This, combined with the winemaker’s choice to leave the skins in during fermentation, is the main reason why Barolo and Barbaresco are perceived as being highly tannic and mouth-drying. To try “the king of red wine” out, we recommend this Barolo from G.D. Vajra, which is a perfect example of a high-tannin wine. Its tannins are often described as “grippy” or “chewy”, adding a wonderful texture to each sip.

Organic vineyards can also lead to thicker skins, as without the use of artificial pesticides, grapes are required to grow thicker skin to protect themselves from pests. For example, take this Cabernet Sauvignon-led blend from Pasanau winery in Spain, which was also grown in poor gravelly soils, leading to a fantastically dry Catalonian red. Cab Sav’s tannins are known for being “muscular” and “angular”, and this blend is no exception.

Low-Tannin Wines

Low- or medium-tannin wines are usually limited within the scope of light red wines. Due to its thin skin, Pinot Noir is a famously difficult grape to grow – it is temperamental and delicate, almost the opposite of Cabernet Sauvignon, which is robust enough to grow all over the world. This small amount of skin in comparison to the pulp is mainly what leads to Pinot Noir being a low-tannin wine. For a great example of a complex wine without too many tannins, we recommend this New Zealand Pinot Noir from Felton Road. Its tannins are best described as being “silky”.

Another famous example of a light low-tannin red wine is Gamay, perhaps best known as the grape behind the greatest wines of the Beaujolais region. This wine from Domaine Thillardon is an excellent low-tannin choice. To use another soft fabric as a metaphor, Beaujolais tannins are sometimes described as “velvety” or “finely grained”.

Tannins in White Wines

White wines are typically made without stems or skins, so they have very few tannins. This is also why red wines can be aged for so much longer than whites. However, in certain styles, tannins can be added via ageing in oak barrels.

Oak-aged whites are often seen in buttery California Chardonnays or white Rioja wines. Take, for example, the Suane Reserva from the Alonso & Pedrajo winery, which was aged in French oak for 13 months.

Its tannins are less obvious than in most red wines – look for hints of oak that dry out the mouth slightly. Even more striking is the unctuous mouthfeel and big structure, which comes from malolactic fermentation in the oak barrels. Its tannins are “barely there”, and its texture is “buttery”.

In the same realm as white wines, you also have orange wines. These are not made with zero skins, but rather a technique that is often called “extended skin contact”. In the process, the wine is left in contact with the skins for some of the process, but not the entire fermentation, as is often the case with red wines. This imparts an orange colour. There is also the unusual case of orange amphora wines – aged in clay with extended skin contact, these can be considerably tannic. We recommend this Rkatsiteli from the Tchotiashvili winery in Georgia. It’s an intriguing wine for those looking to explore tannins. It is “powerful” and “chewy”, with hints of black tea and dried fruits in its profile.

Health Benefits of Tannins

People often get confused between sulfites and tannins, and many people avoid drinking red wine altogether, due to the belief that tannins cause headaches. Approximately 1% of the population have a sulfite sensitivity, so it is possible that the red wine headache you’re experiencing is due to sulfites. However, sulfites and tannins are totally different things. Tannins are naturally occurring compounds, which are also present in chocolate, coffee, tea, or pretty much anything involving plant matter. Depending on the winemaker, sulfites are often added during the winemaking process, and are used to slow down the fermentation process.

In reality, sulfites are mostly harmless, unless you have an allergy. On the other hand, tannins have a host of suspected health benefits. Let’s explore some of them now.

Antioxidant Properties

First of all, tannins from grape stems, seeds, and skins are a good source of polyphenols, which are natural compounds. In turn, polyphenols are antioxidants, eliminating oxidative stress in the body, which has been linked to ageing and chronic diseases. So, in moderation, red wine can be beneficial.

Cardiovascular Benefits

In addition to their antioxidant properties, it has also been proven that polyphenols can reduce blood clots, improve blood vessel function, and enhance blood circulation. When it comes to red wine in particular, there may be some truth behind the notion that a glass of red wine is good for your heart.

Other Potential Benefits

Beyond their antioxidant and cardiovascular effects, research has also suggested that tannins may play a role in reducing inflammation. Mirroring the role that they play in plants, tannins may also be helpful in combating harmful bacteria. Research on tannins in wine is still ongoing, and there are relatively few long-term studies so far – but signs seem to point towards multiple health benefits.

Common Questions About Tannins

Can Tannins Be Reduced in Wine?

There are actually a number of ways to reduce the tannic quality of wines, making them more approachable and drinkable. The first involves waiting: when you age a wine in a cellar, oxidation occurs very slowly, gradually softening the tannins. A more extreme version of this happens the moment you pop the cork – decanting a tannic red wine for an hour or so before drinking can help soften the tannins and bring the fruit flavours to the front. Finally, it also helps to pair tannic wines with fatty foods, like steak. The fat and protein in meat essentially cancel out the tannins, and vice versa.

Tips for Loving Tannins in Wine

Keep an Open Mind

Tannic wines can be an extremely rewarding and gastronomic experience, and developing an appreciation for them starts with an open mind. We recommend drinking all sorts of wines, and paying attention to the bitter and astringent qualities of them all.

Engage Your Senses

It’s fair to say that extremely tannic wines, like Barolo or Cabernet Sauvignon, are an acquired taste. We recommend taking your time with it, and building your way up by trying out low-tannin wines first, like Pinot Noir and Beaujolais. Then, when you sip on a Nebbiolo wine, pay attention to the bitterness and astringent texture – try to discern what it brings to the wine as a whole, and pay attention to how the texture evolves over the course of a glass. By engaging your senses, you can begin to discover the unique character that they bring to every glass, and why wine critics use such words as “grippy”, “polished”, or “dusty” to describe them.

Whether they’re big and rustic, as in an Italian Sangiovese, or barely there at all, tannins are worth exploring. Due to the fact that they contribute a bitter taste, which is often seen as an undesirable trait, they are often overlooked. However, they are a vital part of any great balanced wine, providing a large part of a wine’s overall texture, and they also enable some fantastic food pairings. Gaining an appreciation for tannins is a part of any wine enjoyer’s journey, and we hope this article has given you the tools to do so.

communication en speed ol service